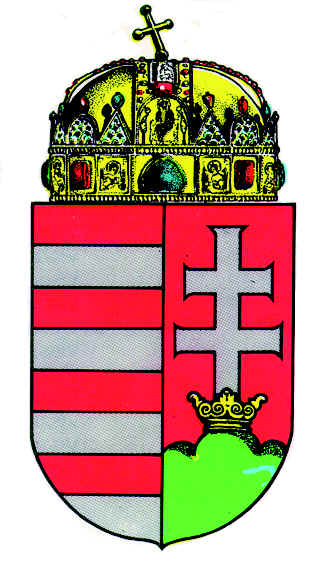

The chief emblem of a country, symbolizing its history, is its national coat of arms. The changes in Hungary's coat of arms duly reflect the main junctures in the nation's history.

Most modern states have coats of arms whose content has been hallowed by long tradition and usage. The scale of the public acceptance gained by a country's coat of arms rests not only on laws and regulations, but on how well its citizens recognize and relate to the devices it contains. A coat of arms is more than a distinctive mark. It is an inclusive image, imbedded in a country's specific national and historical traditions.

In Hungary's case, the oldest component of the historical coat of arms reinstated in 1990 is the patriarchal cross: This became a national symbol some 800 years ago. Having appeared on coins towards the end of the 12th century, it then became part of the coat of arms, on a red field.

The triple mound appeared more than a century later, probably through the new ruling house, which had ties of kinship with Naples. The cross originally stood on three feet, which developed into the mounds.

The bars on the other side of the shield appeared in the late 12th or early 13th century, probably through Spanish influence, as the ruling house had a connection there. The shield has been ensigned with the national crown, which took its place there more than 600 years ago.

The Hungarian coat of arms has undergone many changes. Every device on it can be linked with important struggles. Wars, peace treaties, civil strifes, revolutions, dethronements, the fall of dynasties and systems, and other historical upheavals wrought changes on the coat of arms at the time.The Hungarian Parliament chose to reinstate the country's historical coat of arms in the summer of 1990. This socalled crowned, lesser coat of arms consists of a pointed, impaled shield. The left-hand side ("dexter" as you shelter behind it) has a barry of eight, gules (red) and argent (silver). The other side has a gules field with a patriarchal cross argent rising from a crown (gold) on a triple mound vert (green). The shield is ensigned with the Hungarian Crown.

The flag of the Republic of Hungary is a tricolor of horizontal red, white and green bands.

Use of this flag first gained legal status during the 1848-49 revolution and war of independence against Habsburg rule. Earlier flags had evolved by customary Iaw.

According to some sources, the banners of the Magyars arriving from the East in the 9th century usually bore the device of a turul, a mythical bird resembling an eagle. Later depictions of Hungarian kings usually showed them with banners bearing a patriarchal cross or red and white stripes. This practice continued for several centuries after the reign of St. Stephen, founder of the kingdom (1001-1038).

Hungary's national colors, red, white and green, first appeared together on the cord of a seal in 1618, in the reign of Matthias. They probably arose from the tinctures of the coat of arms.

The tricolor pattern gained popularity from the French Revolution as a type of national flag. The colors were already being used consciously at political gatherings during the great age of reform, in the 1830s and 1840s.

After the early successes in the 1848-49 revolution and war of independence, it was decreed that "the national colors and arms of the country shall be restored to their ancient rights." Red was taken to be a symbol of strength, white of fidelity and green of hope. While Hungary was a kingdom, the royal crown also featured on the national flag.

After 1945, the crown was replaced on the flag by the crownless, so-called Kossuth coat of arms (named after Lajos Kossuth, 1802-1894, one of the greatest l9th-century Hungarian politicians, who led the 1948-9 war of independence and died in exile.) The 1949 constitution replaced this with a crest un-related to tradition and historical continuity. In the Republic of Hungary since the change of system, the ensigned coat of arms with a crown once again adorns the red, white and green national standard.

The institution of kingship in Hungary was established by King Stephen I, who was later canonized. His work of organizing the state and the church was embodied in the royal crown, which he received from Pope Sylvester II in the year 1000. He had himself crowned with it on the first day of the new millennium, while the rest of Europe quaked at the prospect of the end of the world and the coming of Antichrist.

This crown received from the Pope had a double significance. On the one hand it meant that the Hungarian king was spiritually a direct dependant of the Pope, and not, therefore, a vassal of the Holy Roman Emperor. So it symbolized, within bounds, the sovereignty of the kingdom. On the other hand, it was an emblem of secular rule given by the Pope to the king so that he might support the aspirations of the Roman Catholic Church in the country.

In depictions of the time, this crown bears no resemblance to the crown of today. The crown of King Stephen was the kind of jewelled open crown worn by almost all European monarchs at the turn of the millennium.

Although the first crown disappeared, the belief persisted for centuries in Hungary that the Holy Crown was identical with the one donated by the Pope to crown the king who founded the state. So what happened to the original Crown of St Stephen?

The most likely of the many views expressed by historians is that the original Hungarian crown was plundered by Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor. Since Hungarian sovereignty was temporarily suspended at the time, Henry returned the crown to Rome, where it vanished, or at least its fate is unknown.

The present crown, however, is also a relic of St Stephen. It is probably an amalgam of a reliquary for a skull and a Greek crown presented in about 1074 to King Géza I by the Byzantine Emperor Michael Ducas. It is presumed that the Holy Crown known today, symbolizing Hungarian kingship, existed by 1166. So the finest, most radiant relic of Hungarian history is more than 800 years old.

However, the crown went through every conceivable adventure down the ages. There can hardly be another historical art object that has been hidden in as many countries, places, castles, mansions and fortresses.

Battles and wars were fought and thrones toppled for possession of it. On occasions it has been lost while being brought back to Hungary from abroad. There were characters in history who simply purloined it, and others who kept it in secret. It has even been pawned, and buried during flight. It has been taken out of the country many times, and on each occasion, its return was a cause for solemn, national celebration. A special institution was set up to protect it, with guards chosen from the highest men in the land and a special military detachment.

Supporters of the extreme right-wing Hungarian government at the end of the Second World War took the crown to the West, where it came into the hands of the US military. The crown and other crown jewels were then kept in the United States, and some repairs even done to them, until 1978, when Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, at the behest of President Carter, ceremoniously returned them to Hungary. Since then, the crown and regalia have been on public display at the Hungarian National Museum.

As the picture shows, the crown has two parts. Most researchers agree that these were merged in the last quarter of the l2th century.

On the lower part of the crown, which is of Greek origin, one of the enamel plates shows the bust of a king with the legend in Greek, "Géza, Loyal King of Turkia" (i.e. Hungary). On the king's head is a diadem that resembles the lower part of the crown without its upper parts and pendants. This, as mentioned, was presented by the Byzantine emperor to Géza, whose consort was the daughter of a Byzantine patrician. The upper part of the present crown closely resembles a medieval reliquary for a skull. In its original form, the bands forming a cross may have been adorned with pictures of the twelve apostles, surmounted by a plate holding the four bands together and bearing a picture of Christ Enthroned. When the reliquary was incorporated into the crown, one panel was cut from each band, leaving a total of eight pictures of apostles.

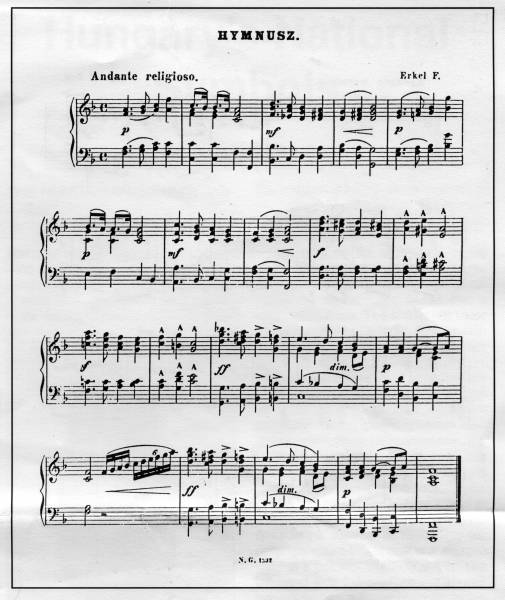

The text of the Hungarian national anthem was written in 1823 by Ferenc Kölcsey (1790-1838), one of the great poets of the age of reform. It was first published in 1828 under the title Hymn.

The music was composed by the composer and conductor Ferenc Erkel (1810-1893) in 1844, when he won a contest to compose the national anthem. It was first performed in the National Theatre in Pest in 1844, but only adopted officially as the national anthem in 1903.

The Hymn has eight stanzas, although only the first is normally played or sung on official occasions. The translation made in 1881 by William N. Loew provides some inkling of the lyrics.

O my God, the Magyar bless

With Thy plenty and good cheer!

With Thine aid his just cause press,

Where his foes to fight appear.

Fate, who for so long didst frown,

Bring him happy times and ways;

Atoning sorrow hath weighed down

Sins of past and future days.

By Thy help our fathers gained

Karpat's proud and sacred height;

Here by Thee a home obtained

Heirs of Bendegúz, the knight.

Where'er Danube's waters flow

And the streams of Tisza swell,

Arpád's children, Thou dost know,

Flourished and did prosper well.

For us let the golden grain

Grow upon the fields of Kún,

And let Nectar's silver rain

Ripen grapes of Tokay soon.

Thou our flags hast planted o'er

Forts where once wild Turks held sway;

Proud Vienna suffered sore

From King Mátyás' dark array.

But, alas! for our misdeed,

Anger rose within Thy breast,

And Thy lightnings Thou didst speed

From Thy thundering sky with zest.

Now the Mongol arrow flew

Over our devoted heads;

Or the Turkish yoke we knew,

Which a free-born nation dreads.

Oh, how often has the voice

Sounded of wild Osman's hordes,

When in songs they did rejoice

O'er our heroes' captured swords!

Yea, how often rose thy sons,

My fair land, upon thy sod,

And thou gavest to these sons,

Tombs within the breast they frod!

Though in caves pursued he lie,

Even there he fears attacks.

Coming forth the land to spy,

Even a home he finds he lacks.

Mountain, vale-go where he would,

Grief and sorrow all the same-

Underneath a sea of blood

While above a sea of flame.

'Neath the fort, a ruin now,

Joy and pleasure erst were found,

Only groans and sighs, I trow,

In its limits now abound.

But no freedom's flowers return

From the spilt blood of the dead,

And the fears of slavery burn,

Which the eyes of orphans shed.

Pity, God, the Magyar, then,

Long by waves of danger tossed;

Help him by Thy strong hand when

He on grief's sea may be lost. Fate,

who for so long did frown,

Bring him happy times and ways;

Atoning sorrow hath weighed down

All the sins of all his days.